Building SmartBooksAI: How I Learned to Think in Vectors

I recently took a LinkedIn course on AI Engineering to better understand how semantic embeddings and vector databases work. The course was well done and helped me get into the technical weeds of RAG, cosine similarity, and vector indexing. But when it was over, I had that nagging feeling of understanding theoretically without truly getting it.

So I decided to build something.

SmartBooksAI is a semantic search and analytics platform built on top of my personal Goodreads data. It uses vector embeddings to transform a static CSV export of every book I’ve read and want to read into an intelligent recommendation engine where I can explore my reading universe in 3D space.

SmartBooksAI Galaxy View showing books as stars in 3D space

The project taught me something unexpected: semantic search is incredibly powerful on its own. I started this project thinking I’d need to build a full RAG architecture with LLM API calls to get intelligent recommendations. But once I had the embeddings working, I realized the vector similarity alone was delivering exactly what I needed.

From Exact Match to Semantic Search

One of the key takeaways from the course was this idea:

We are moving from structuring data for deterministic retrieval to structuring it for probabilistic reasoning.

As a data professional, I’ve spent years structuring data in relational databases to optimize for exact matches. Something like:

SELECT * FROM books WHERE genre = 'Sports' AND title LIKE '%Running%';

This works when you know exactly what you’re looking for. But that’s not always how I discover books. Sometimes I want “a sci-fi book similar to Ready Player One” or “something with the same energy as Atomic Habits.” Keywords fail here because they match on text, not meaning.

Vector databases solve this by storing data as numerical representations of semantic meaning. Instead of matching on column values, you search by conceptual proximity. A relational database can’t do this because it can’t calculate “nearness” of intent.

| Relational Database | Vector Database | |

|---|---|---|

| Optimized for | Exact matches | Conceptual similarity |

| Query style | WHERE genre = 'business' | ”gritty underdog startup stories” |

| Relationships | Foreign keys & joins | Geometric proximity |

| Strength | Structured, deterministic | Semantic, probabilistic |

What Are Vector Embeddings?

Embeddings are dense numerical vectors that represent data in a way that captures semantic meaning. You take text (a book description, for example) and transform it into a list of numbers. Each number represents some learned feature of the text’s meaning. The result is a coordinate in high-dimensional space.

Books with similar themes, tones, and concepts end up with similar coordinates. Books with different content point in different directions.

A Concrete Example: The Road to Sparta

📖 Here is what happens when the embedding model processes the book The Road to Sparta:

Input:

“The Road to Sparta is the story of the 153-mile run from Athens to Sparta that inspired the marathon and saved democracy, as told—and experienced—by ultramarathoner and New York Times bestselling author Dean Karnazes. In 490 BCE, Pheidippides ran for 36 hours straight from Athens to Sparta to seek help in defending Athens from a Persian invasion in the Battle of Marathon. In doing so, he saved the development of Western civilization and inspired the birth of the marathon as we know it. Genres: Sports, History, Memoir”

Output: A 384-dimensional vector:

[0.23, -0.15, 0.89, 0.02, -0.44, ... ](× 384 values)

These numbers are not random. They encode the semantic meaning of the book: ancient Greece, heroism, physical endurance, running, epic journeys, and warfare. And every other book in my library goes through the same process.

Cosine Similarity: Measuring Semantic Distance

Once every book is a vector, you need a way to compare them. Cosine similarity measures the angle between two vectors on a scale from 0 (unrelated) to 1 (identical meaning).

This single score is how the system decides which books are “close” to each other. It is measuring the angle between two vectors in 384-dimensional space.

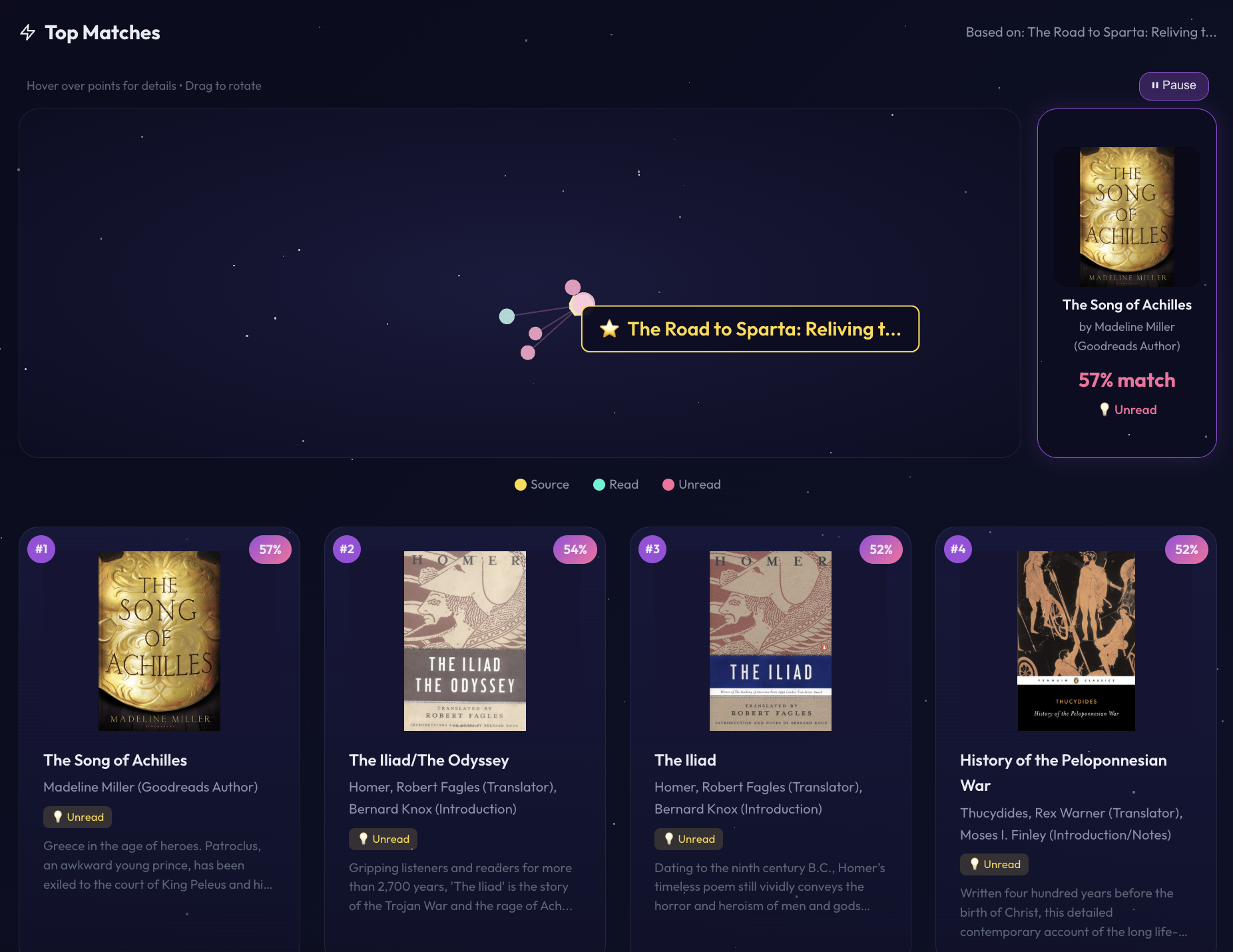

Here are the actual similarity scores for The Road to Sparta:

- Rank #1: The Song of Achilles (Madeline Miller) → 0.57 similarity

- Both centered on ancient Greek heroism, warfare, and epic journeys

- Rank #2: The Iliad/The Odyssey (Homer) → 0.54 similarity

- Ancient Greek epics, warriors, legendary journeys, and heroism

- Rank #12: Born to Run (Christopher McDougall) → 0.45 similarity

- Both about running culture and endurance (different semantic cluster)

What’s interesting is that books can overlap semantically for different reasons. The Road to Sparta has two strong themes: Greek culture/history AND running. So the top matches include ancient Greek literature (matching on the historical dimension) while other running books like Born to Run by Christopher McDougall appear further down the list (matching on the endurance sports dimension). The embedding model captured both aspects, showing how a single book can live at the intersection of multiple semantic clusters.

How SmartBooksAI Works

The app has five stages. Each one builds on the previous.

Stage 1: Collect

I started with two data sources:

- My Goodreads CSV export: 416 books I’ve read

- Kaggle’s Best Books Ever dataset: ~10,000 books with rich metadata (descriptions, genres, cover images)

The Goodreads export has titles and authors but sparse descriptions. The Kaggle dataset fills in the gaps.

Stage 2: Enrich

To get the most out of embeddings, I needed rich context for each book: not just a title and author, but descriptions, genres, and series information. The richer the input, the better the semantic representation.

💡 From the AI Eng course: text extraction quality sets the ceiling for downstream AI tasks. If the data going into embeddings is thin, the search results coming out will be too.

I used a waterfall enrichment strategy to maximize metadata coverage:

- Pass 1: Match on ISBN13 (high precision)

- Pass 2: Match on normalized Title + Author (high recall for unmatched books)

Result: 99.6% enrichment. 9,750 of 9,785 books matched with full metadata.

Stage 3: Embed

This is where text becomes geometry.

Each book’s combined text (title, author, description, and genres) gets passed through an embedding model called all-MiniLM-L6-v2 from the Sentence Transformers library. I chose this model because it runs locally, it is fast (~50ms per book), and it is widely used in production RAG systems.

The output is a 384-dimensional vector per book. Across my full library, that is 9,785 books × 384 dimensions = 3,757,440 embedding values.

To make this tangible, let me walk through an example.

📖 Harry Potter in Vector Space

Take Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. The embedding model processes the full text representation: magical tournament, dark forces rising, friendship tested, coming-of-age at a school for wizards. It outputs a 384-dimensional vector that encodes all of that meaning into numbers.

Every other Harry Potter book goes through the same process. And because they share the same world, characters, themes, and narrative style, they end up with very similar vectors. In 384-dimensional space, the Harry Potter series forms a tight cluster.

The nearest neighboring cluster? The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis. The model picked up on shared themes: portal fantasy, good vs. evil, young protagonists, magical worlds, and coming-of-age journeys.

The next closest cluster? The Lord of the Rings trilogy by J.R.R. Tolkien. This makes perfect sense: epic fantasy worlds, quests, magic, good vs. evil, and rich world-building. The model has never been told these books are related. It figured it out from the book description text alone.

Galaxy View showing Harry Potter cluster with nearby fantasy books

Meanwhile, on the other side of the galaxy, my business and self-improvement books (Zero to One, The Law of Success, Deep Work) form their own dense cluster, far from the fantasy section. The 3D map makes what would otherwise be abstract math feel intuitive.

Stage 4: Reduce

Humans can’t visualize 384 dimensions. To build the interactive Galaxy View, I needed to compress those vectors down to three dimensions while preserving the relationships between books.

The tool for this is UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection), a dimensionality reduction algorithm that preserves local structure. Books that are close in 384D stay close in 3D. Clusters hold together. The Harry Potter group remains a tight formation even after the compression.

The vectors themselves are stored in ChromaDB, an open-source vector database optimized for similarity search. It handles the indexing under the hood using Approximate Nearest Neighbors (ANN) so you don’t have to compare every query against all 10,000 vectors. Query time: <200ms.

💡 From the AI Eng course: it is common to scale vector databases from thousands to millions to billions of vectors. My library sits at the thousands level, with plenty of room to grow.

Stage 5: Serve

The frontend is a React app with TypeScript. Three.js powers the 3D Galaxy View. The result is a fully interactive experience with semantic search, reading analytics, and personalized recommendations, all running at <200ms search latency.

Why Vector Search Matters for AI

Vector databases and semantic search aren’t new. Google released Word2Vec in 2013, a breakthrough word-embedding solution that revolutionized how search engines understand meaning. The technology has been around for over a decade.

But vector search has become essential with the rise of Large Language Models. LLMs are trained on massive amounts of general knowledge, but they don’t know about your specific data. They can’t answer questions about your personal library, your company’s documents, or your proprietary datasets. And they have a context window limit (typically 128K-200K tokens), so you can’t just dump your entire dataset into the prompt.

This is where RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) comes in:

User: "What should I read if I loved 'A Tale of Two Cities'?"

↓

[1] Query gets embedded into a vector (same model as your data)

↓

[2] Vector database finds the most relevant books via similarity search

↓

[3] RAG framework (like LlamaIndex) builds a prompt with those books as context

↓

[4] LLM generates a natural language answer using the retrieved context

↓

"Because you enjoyed 'A Tale of Two Cities', I'd recommend 'Great Expectations'. Both are Dickens novels set in Victorian England exploring themes of social class, redemption, and sacrifice through richly drawn characters."

The key word is Augmented. The LLM doesn’t just answer from its training data. It answers from your data: your library, your ratings, your domain-specific information. That’s what makes AI applications personal and useful.

Vector databases are the bridge that makes this pattern work at scale. They enable fast semantic retrieval (sub-200ms) across millions of documents, making it possible to build AI applications that feel responsive while remaining grounded in real data.

💡 From the AI Eng course: There is a latency vs. accuracy tradeoff in semantic search. Hybrid search (combining vector similarity with BM25 keyword matching) often provides the best balance, catching both conceptual matches and exact terms. This is the pattern used in most production RAG systems.

The Unexpected Discovery

I built SmartBooksAI to find more books I’d love. And it delivered. The My Taste Profile feature averages the embeddings of all my 5-star books (89 of them) into a single centroid vector, then searches my to-read list for the nearest unread neighbors. The recommendations were on point: some books I’d never heard of but that sounded up my alley.

SmartBooksAI Discover tab showing My Taste Profile feature

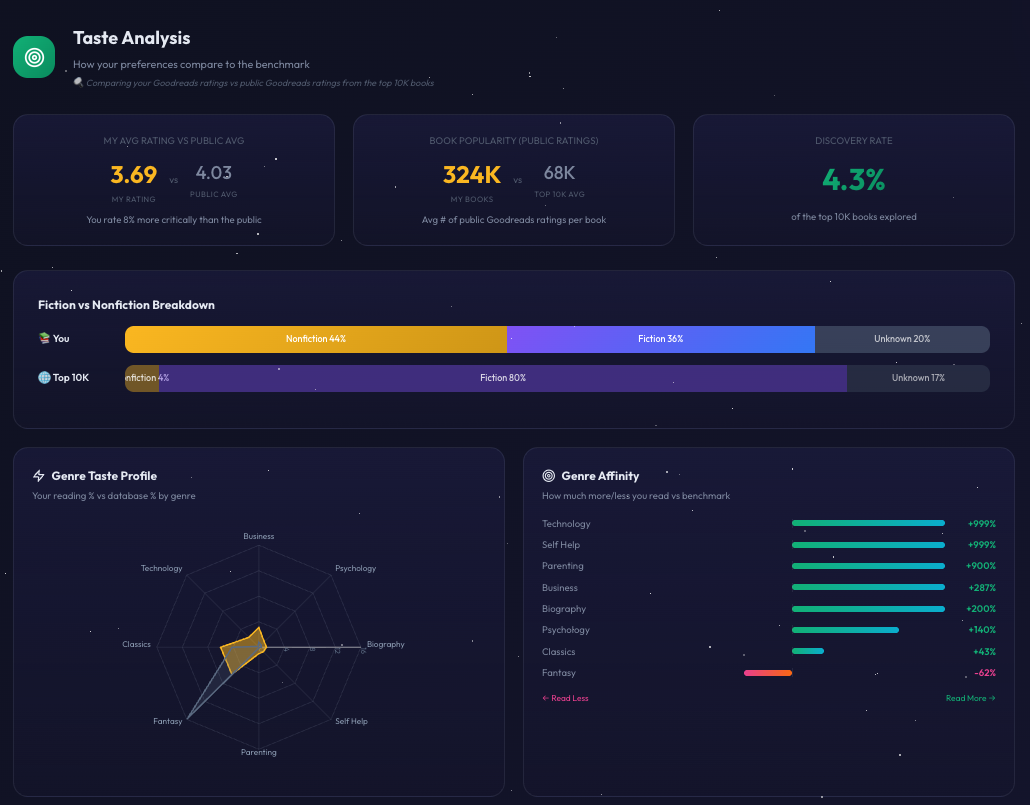

But I also had a surprising realization. When I zoomed out to see my full library plotted in 3D space, my 5-star books formed a dense cluster, heavily weighted toward business nonfiction, self-improvement, and technology. Huge regions of the galaxy sat completely dark.

I’ve always thought of myself as a fairly well-rounded reader. The vectors disagreed. My wife, who has been telling me I read too many boring nonfiction books, was vindicated. In 3D. With math.

Designing for Serendipity

This insight shifted how I thought about the tool. Semantic similarity is powerful, but it can also reinforce an echo chamber. If I only search for books like the ones I already love, I’ll keep reading in the same narrow band of the galaxy.

My taste analysis tab highlighted that compared to the popular database, I was significantly underepresented in fantasy.

So I built a Branch Out feature: find books that share the deeper themes I tend to enjoy (systems thinking, resilience, big ideas) but that exist in a different quadrant of the map and a different genre. The algorithm looks for high taste similarity combined with high spatial distance.

The result: recommendations that feel unexpected but not random. Books I’d never think to pick up but that connect to what I care about in ways I can’t see from browsing a shelf. I’ve already added the fantasy book “Ink and Bone” by Rachel Caine to my library list and we will see how well the recommendation system worked based pending my Goodreads rating. Maybe I’ll even tag recommended books as such for a self-learning feedback loop.

Building With AI

I used AI to build essentially all of this in a few hours.

Claude Opus 4.5 handled the architecture decisions: system design, data pipeline structure, project scaffolding. Claude Sonnet 4.5 handled feature development and UI iteration. It’s significantly cheaper, which matters when you’re making dozens of small changes.

The process was remarkably smooth. I described what I wanted conceptually and AI translated it to working code.

💡 From the AI Eng course: the AI engineer’s role is shifting toward building data processing pipelines, making architectural decisions, and integrating language models.

Five hours of the AI Engineering course content gave me the vocabulary. One weekend of building gave me the intuition. If you’re trying to learn how embeddings or RAG pipelines work, I’d recommend building something with your own data. You’ll know immediately if the results are good because you have the domain expertise to evaluate them.

What I Took Away

✅ Think geometry, not rows. In a vector database, you’re searching for neighbors in space, not matching values in columns. The query itself becomes a vector.

✅ Embeddings are your schema. In SQL, the schema defines structure. In vectors, the embedding model defines how meaning gets encoded. It’s foundational.

✅ Similarity is approximate. Vector search uses probabilistic algorithms (ANN). You’re not getting exact matches. You’re getting the closest neighbors.

✅ Metadata still matters. Hybrid search (vector + keyword) often outperforms pure vector search alone. Genre tags, ratings, and dates are still valuable for filtering. The relational mindset doesn’t go away; it gets augmented.

✅ Build to learn. I started this project thinking I’d need a full RAG pipeline and instead realized semantic search was all I needed. AI concepts feel abstract until you build something tangible with your own data.

- Zach

The Tech Stack

| Component | My Choice | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Embedding Model | Sentence Transformers (all-MiniLM-L6-v2) | Convert text → 384D vectors |

| Vector Database | ChromaDB | Store and search embeddings |

| Dimensionality Reduction | UMAP | 384D → 3D for Galaxy View |

| Frontend | React + TypeScript + Three.js | Interactive 3D experience |

| Hosting | Netlify | Static deployment |

GitHub: All code and pipeline scripts are documented in my SmartBooksAI repo.